Let's build a Full-Text Search engine

这是一篇转载文章原文地址,原文讲述如何构建一个全文搜索引擎,用的 Go 实现的,本来想翻译一下,顺便用 Java 实现一下,由于翻译出来比较生硬,还是把原文放出来,顺便把我用 Java 实现的版本放在链接中Java实现版本。

Full-Text Search is one of those tools people use every day without realizing it. If you ever googled “golang coverage report” or tried to find “indoor wireless camera” on an e-commerce website, you used some kind of full-text search.

Full-Text Search (FTS) is a technique for searching text in a collection of documents. A document can refer to a web page, a newspaper article, an email message, or any structured text.

Today we are going to build our own FTS engine. By the end of this post, we’ll be able to search across millions of documents in less than a millisecond. We’ll start with simple search queries like “give me all documents that contain the word cat“ and we’ll extend the engine to support more sophisticated boolean queries.

Note

Most well-known FTS engine is Lucene (as well as Elasticsearch and Solr built on top of it).

Why FTS

Before we start writing code, you may ask “can’t we just use grep or have a loop that checks if every document contains the word I’m looking for?“. Yes, we can. However, it’s not always the best idea.

Corpus

We are going to search a part of the abstract of English Wikipedia. The latest dump is available at dumps.wikimedia.org. As of today, the file size after decompression is 913 MB. The XML file contains over 600K documents.

Document example:

<title>Wikipedia: Kit-Cat Klock</title> |

Loading documents

First, we need to load all the documents from the dump. The built-in encoding/xml package comes very handy:

import ( |

Every loaded document gets assigned a unique identifier. To keep things simple, the first loaded document gets assigned ID=0, the second ID=1 and so on.

First attempt

Searching the content

Now that we have all documents loaded into memory, we can try to find the ones about cats. At first, let’s loop through all documents and check if they contain the substring cat:

func search(docs []document, term string) []document { |

On my laptop, the search phase takes 103ms - not too bad. If you spot check a few documents from the output, you may notice that the function matches caterpillar and category, but doesn’t match Cat with the capital C. That’s not quite what I was looking for.

We need to fix two things before moving forward:

Make the search case-insensitive (so Cat matches as well).

Match on a word boundary rather than on a substring (so caterpillar and communication don’t match).

Searching with regular expressions

One solution that quickly comes to mind and allows implementing both requirements is regular expressions.

Here it is - (?i)\bcat\b:

- (?i) makes the regex case-insensitive

- \b matches a word boundary (position where one side is a word character and another side is not a word character)

func search(docs []document, term string) []document { |

Ugh, the search took more than 2 seconds. As you can see, things started getting slow even with 600K documents. While the approach is easy to implement, it doesn’t scale well. As the dataset grows larger, we need to scan more and more documents. The time complexity of this algorithm is linear - the number of documents required to scan is equal to the total number of documents. If we had 6M documents instead of 600K, the search would take 20 seconds. We need to do better than that.

Inverted Index

To make search queries faster, we’ll preprocess the text and build an index in advance.

The core of FTS is a data structure called Inverted Index. The Inverted Index associates every word in documents with documents that contain the word.

Example:

documents = { |

Below is a real-world example of the Inverted Index. An index in a book where a term references a page number:

Text analysis

Before we start building the index, we need to break the raw text down into a list of words (tokens) suitable for indexing and searching.

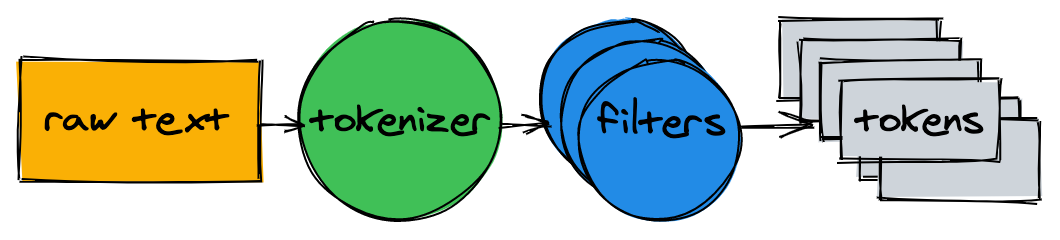

The text analyzer consists of a tokenizer and multiple filters.

Tokenizer

The tokenizer is the first step of text analysis. Its job is to convert text into a list of tokens. Our implementation splits the text on a word boundary and removes punctuation marks:

func tokenize(text string) []string { |

> tokenize("A donut on a glass plate. Only the donuts.") |

Filters

In most cases, just converting text into a list of tokens is not enough. To make the text easier to index and search, we’ll need to do additional normalization.

Lowercase

In order to make the search case-insensitive, the lowercase filter converts tokens to lower case. cAt, Cat and caT are normalized to cat. Later, when we query the index, we’ll lower case the search terms as well. This will make the search term cAt match the text Cat.

func lowercaseFilter(tokens []string) []string { |

> lowercaseFilter([]string{"A", "donut", "on", "a", "glass", "plate", "Only", "the", "donuts"}) |

Dropping common words

Almost any English text contains commonly used words like a, I, the or be. Such words are called stop words. We are going to remove them since almost any document would match the stop words.

There is no “official” list of stop words. Let’s exclude the top 10 by the OEC rank. Feel free to add more:

var stopwords = map[string]struct{}{ // I wish Go had built-in sets. |

> stopwordFilter([]string{"a", "donut", "on", "a", "glass", "plate", "only", "the", "donuts"}) |

Stemming

Because of the grammar rules, documents may include different forms of the same word. Stemming reduces words into their base form. For example, fishing, fished and fisher may be reduced to the base form (stem) fish.

Implementing a stemmer is a non-trivial task, it’s not covered in this post. We’ll take one of the existing modules:

import snowballeng "github.com/kljensen/snowball/english" |

> stemmerFilter([]string{"donut", "on", "glass", "plate", "only", "donuts"}) |

Note

A stem is not always a valid word. For example, some stemmers may reduce airline to airlin.

Putting the analyzer together

func analyze(text string) []string { |

The tokenizer and filters convert sentences into a list of tokens:

> analyze("A donut on a glass plate. Only the donuts.") |

The tokens are ready for indexing.

Building the index

Back to the inverted index. It maps every word in documents to document IDs. The built-in map is a good candidate for storing the mapping. The key in the map is a token (string) and the value is a list of document IDs:

type index map[string][]int |

Building the index consists of analyzing the documents and adding their IDs to the map:

func (idx index) add(docs []document) { |

It works! Each token in the map refers to IDs of the documents that contain the token:

map[donut:[1 2] glass:[1] is:[2] on:[1] only:[1] plate:[1]] |

Querying

To query the index, we are going to apply the same tokenizer and filters we used for indexing:

func (idx index) search(text string) [][]int { |

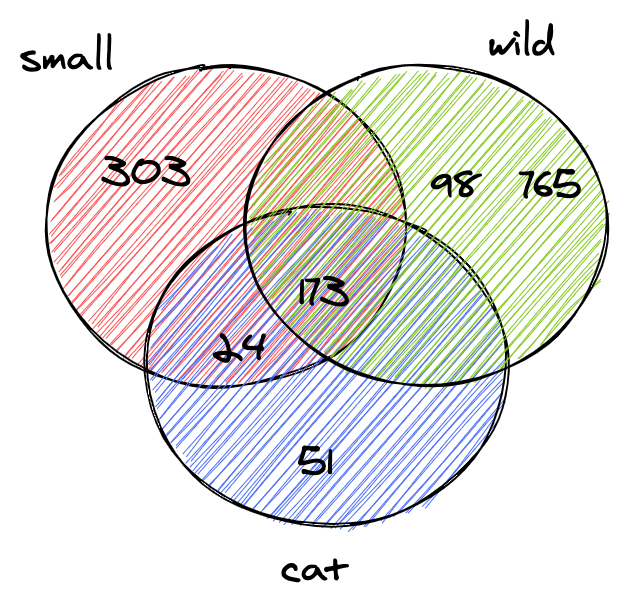

> idx.search("Small wild cat") |

And finally, we can find all documents that mention cats. Searching 600K documents took less than a millisecond (18µs)!

With the inverted index, the time complexity of the search query is linear to the number of search tokens. In the example query above, other than analyzing the input text, search had to perform only three map lookups.

Boolean queries

The query from the previous section returned a disjoined list of documents for each token. What we normally expect to find when we type small wild cat in a search box is a list of results that contain small, wild and cat at the same time. The next step is to compute the set intersection between the lists. This way we’ll get a list of documents matching all tokens.

Luckily, IDs in our inverted index are inserted in ascending order. Since the IDs are sorted, it’s possible to compute the intersection between two lists in linear time. The intersection function iterates two lists simultaneously and collect IDs that exist in both:

func intersection(a []int, b []int) []int { |

Updated search analyzes the given query text, lookups tokens and computes the set intersection between lists of IDs:

func (idx index) search(text string) []int { |

The Wikipedia dump contains only two documents that match small, wild and cat at the same time:

> idx.search("Small wild cat") |

The search is working as expected!

By the way, this is the first time I hear about catopuma, here is one of them:

Conclusions

We just built a Full-Text Search engine. Despite its simplicity, it can be a solid foundation for more advanced projects.

I didn’t touch on a lot of things that can significantly improve the performance and make the engine more user friendly. Here are some ideas for further improvements:

- Extend boolean queries to support OR and NOT.

- Store the index on disk:

- Rebuilding the index on every application restart may take a while.

- Large indexes may not fit in memory.

- Experiment with memory and CPU-efficient data formats for storing sets of document IDs. Take a look at Roaring Bitmaps.

- Support indexing multiple document fields.

- Sort results by relevance.

The full source code is available on GitHub.

I’m not a native English speaker and I’m trying to improve my language skills. Feel free to correct me if you spot any spelling or grammatical error!